It’s not too often these days that a highway case makes the giddy heights of the High Court but our recent case of O’Connor v Luton BC did just that. We and Zurich Municipal defended this

£1.5m claim on behalf of Luton and won both on the defect not being a danger and on causation.

The Claimant was a motorcyclist who lost control of her motorbike when exiting a petrol station forecourt in Luton. She was intending to re-join the main carriageway as part of a convoy of four motorcyclists from her motorcycle club but instead lost control and veered across both lanes into an oncoming vehicle. The Claimant had no memory of the accident but one of the other motorcycle riders said that her back wheel had dropped into a rut on the crossover at the point where the forecourt exit met the road, and this had caused the loss of control. The Claimant contended that the area of deterioration at that point constituted a dangerous defect and breach of Section 41 of the Highways Act 1980.

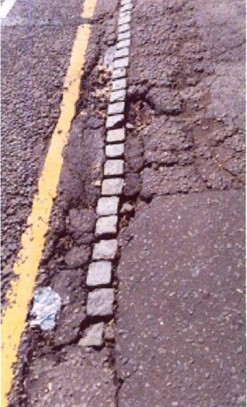

A photograph taken shortly after the accident was replicated in the judgment and it’s worth reprinting here:

Was the defect a danger?

The highways experts were agreed on large parts of the evidence, including a probable measurement of up to 50mm depth for the potholes, and that the deterioration should at least have been noted in the inspection records for the Council.

However, the Defendant’s highways manager and inspector denied the area posed a danger, which was supported by the lack of prior complaints or reports. The Defendant’s highways expert confirmed that although it should have been noted, it was not in fact a dangerous defect when a risk-based approach was taken, pointing out that it was located right at the edge of the footway and carriageway.

Mr Justice Spencer agreed with that analysis. He took account of the greater vulnerability of motorcyclists but confirmed they have a greater choice as to which part of the highway to use. The defect in this case could be easily avoided, particularly considering the low speed at that point. He was also persuaded by the fact that none of the police who attended to investigate the road accident had noted the defect as a potential cause, despite examining the area thoroughly.

Taking everything into account, Mr Justice Spencer found that even if the Claimant had ridden over this area and lost control as a result, the claim would nevertheless have failed because the highway was not dangerous.

Causation: did the pothole cause the loss of control?

Mr Justice Spencer found that a process of slip and re-grip had caused the loss of control. This is a process where the rear wheel (which provides the power) may lose traction for various reasons, then as traction is regained the motorcycle lurches forward. However, there are several possible causes for loss of traction, including loose or slippery stone setts, poor control of the machine, or a contaminant on the rear tyre.

The Claimant’s case relied on the evidence of one witness who claimed to have seen the wheel in the rut. However, the evidence was undermined by:

- The witness not mentioning the deterioration to the police on the night of the accident.

- The witness not reporting the defect to the council at any point.

- The witness walking the forecourt on the night of the accident to look for contaminants, a redundant exercise if the witness was so sure of the cause of the loss of control.

- The extreme description of the loss of control being called into question by the measured evidence from the Defendants’ accident reconstruction and motorbike handling experts.

- The Claimant had also argued that the deterioration was in the natural line of a motorcycle exiting to turn left.

Mr Justice Spencer found that he could not be satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the Claimant had travelled over the area in question. In fact a more likely explanation was to be found in the witness’s evidence, as he confirmed that he had used the garage a few weeks prior but exited at a different point and still almost lost control.

The Judge found that the overall structure of the garage exit, including the camber, different surfaces, and the line of granite setts cause some difficulty for motorcycle riders. This, potentially coupled with poor clutch control, was more likely to have been responsible for the cause of the Claimant’s loss of control.

The Judge also found that while the defect may have been in the natural line for cars turning left, motorcycles are much smaller vehicles and have greater choice as to the part of the exit they use. A motorcyclist could sensibly have avoided a defect rather than ridden over it.

Lessons to be learnt

This is a useful High Court authority on potholes and the issue of dangerousness. In addition, however, it is tempting with a highways claim to jump straight to assessing whether there is a Section 41 breach and/or a Section 58 defence. But causation can be a hugely important preliminary question that should not be overlooked, particularly in a case where the injured Claimant might not remember the accident themselves.

When considering dangerousness and Section 41 breach, consider all factors on a risk-based approach and not just the intervention levels. In this case both highways experts conceded that the measurements may have met the Council’s intervention levels, but the location of the defect was crucial. When taking all the factors into account the Judge agreed that the defect was not dangerous.