Gemma Leonard, Head of Residential at DAC Beachcroft, asked Paul Swinney, Director at think tank Centre for Cities about the factors and patterns that influence the mix and his views on the future formula for mixed use.

In his response Paul takes Leeds as a particular example. However the need to understand variables in disposable income, the level of self-sufficiency of surrounding towns, educational attainment and the importance of a strong regional centre are points common to all.

The prosperity of a place, and the knock-on impact this has on the demand for space in and performance of the high street in that place depends on two main things: the strength of the economy in that place and the strength of other places within commutable distance. Looking at Leeds and its surroundings illustrates this.

|

Box 1: Defining cities and towns

|

Leeds is a provider of prosperity to its surrounding towns

As the biggest city in North and West Yorkshire, Leeds plays a central role in the wider economy. Home to many hundreds of thousands of jobs, it accounts for around 36 per cent of all economic output in its wider area. It is a centre of high-knowledge production in particular, being home to half of the wider area’s knowledge-intensive business services jobs in the private sector.

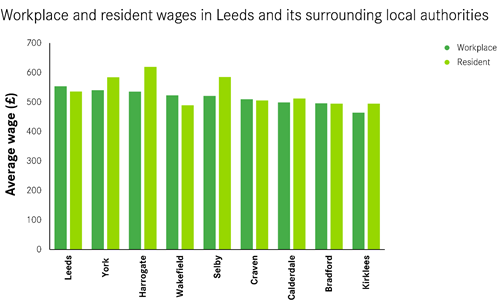

This creates benefits for not just residents in the city but also for those living around it. The most recent data* indicates the wages of workers in Leeds were higher than the wages of its residents. This tells us that higher-paid jobs in Leeds were disproportionately being done by people who lived outside of the city. On the flip side, resident wages were higher in Harrogate and York, with residents here benefitting the most from high-paid jobs elsewhere.

Figure 1: Leeds provides prosperity to its wider area through access to high-paid jobs

Source: ONS

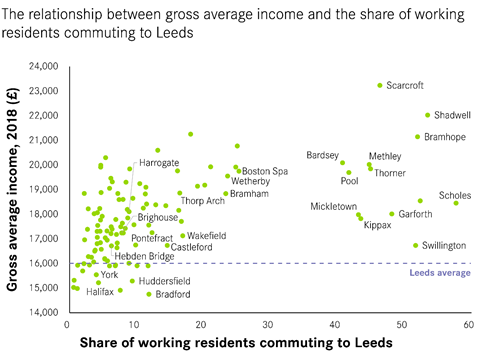

There isn’t data available to understand where specifically these higher-paid commuters live outside of Leeds. But combining the latest available data on commuting, with resident incomes fills in some of the picture (see Figure 2).

It shows that:

- Residents of most of the surrounding towns and villages of Leeds have higher average incomes than Leeds residents.

- And the higher the share of working residents who commuted to Leeds the higher the incomes of people living in these towns and villages.

Combining this data with the findings from Figure 1 suggests that the stronger the commuting links with Leeds, the more prosperous a surrounding town is. A strong Leeds benefits the wider area.

Figure 2: Those places with higher commuting to Leeds tend to have higher incomes

Source: ONS; Census 2011

The benefits don’t all flow one way. Of the 210,000 high-skilled1 jobs in Leeds, almost half (46 per cent) of them were taken by people who lived outside of the city. This underlines the scale of opportunity Leeds provides, but also shows the importance of surrounding areas in supplying Leeds with high-skilled workers.

Some towns are more reliant on Leeds than others

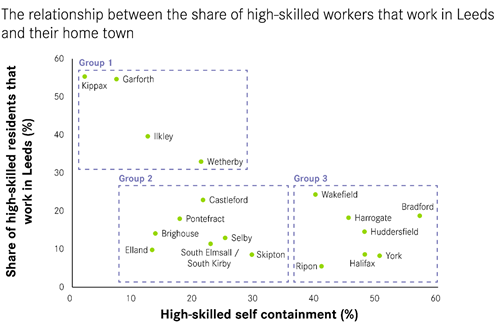

How reliant other towns are on the prosperity Leeds provides depends in part on the strength of their economies in their own right. To give an indication of this, Figure 3 takes two metrics – how many high-skilled people commute to Leeds and how many high-skilled people work within their own town – in all places with a population higher than 10,000 people.2

Figure 3: Some places are more reliant on Leeds for high-skilled jobs than others

Source: Census 2011

It reveals three groups of places. The first is the group to the top left of the chart – Kippax, Garforth, Ilkley and Wetherby – that are both close to and are largely dependent on Leeds. At least a third of all their high-skilled working residents work in Leeds, much higher than the share both living and working within their respective towns. As well as having relatively high average incomes, their strong employment outcomes suggest that their proximity to Leeds is beneficial.

The second is the group to the bottom left. The residents of these places, such as Castleford, Selby and Skipton, are dependent on places around them to provide high-skilled job opportunities (shown by their low high-skilled self-containment rates) but this isn’t primarily supplied by Leeds. Both their incomes and their employment outcomes are worse than for those towns in Group 1.

The third group is to the bottom right and is made up of places that are less dependent on Leeds. For four of these places this is no surprise given their scale – Bradford, Wakefield, Huddersfield and York are all within Centre for Cities’ list of the 63 largest urban areas in the UK and are large economies in their own right. But three – Harrogate, Halifax and Ripon – are smaller towns. The income and employment outcomes are varied across these three places. Harrogate, and to a lesser extent Ripon, have higher incomes and strong employment outcomes, suggesting their own economies provide a strong source of prosperity. Halifax is one exception, where incomes are amongst the lowest of all the towns in the area, and employment outcomes the worst.

These patterns affect the use of land in town centres

High Street Vacancy Rates and Rents

The amount of disposable income that people have to spend, which will be determined in large part by the trends above, has implications for the use of space in their town centres and the number of vacant shops. Using the number of vacant retail and leisure units in the town centres as a measure of success reveals that, for the places where data is available, stronger employment outcomes for residents and higher incomes are related to lower shop vacancy rates. This is especially the case for the smaller towns in the immediate orbit of Leeds.

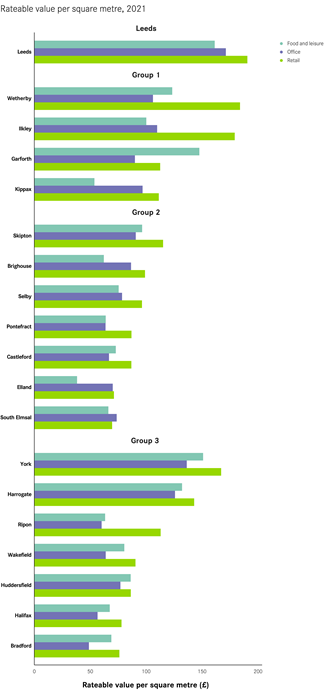

Reflecting this, the rents (proxied by rateable values) vary across these places. For retail in particular, the Group 1 towns of Wetherby and Ilkley have some of the highest values (close to those in Leeds city centre). Group 2 towns such as Elland and South Elmsall/South Kirby tend to have the lowest rents. And Group 3 show a mix, with Harrogate having high rents but Halifax having lower rents. In terms of offices, Harrogate town centre has the highest rents of any of the town centres in Group 3. This is reflective of the town’s stronger, more independent economy where office space is in demand.

Figure 4: Varying rents show how demand for town centre space varies

Source: Valuations Office Agency

Commercial Space Composition

In terms of supply of commercial space, the make-up of space in Leeds city centre looks very different to the surrounding centres. Offices are the dominant use in the centre of Leeds, with 2.3 square metres of office space to every 1 square metre of retail space. This reflects the role it plays in providing high-skilled knowledge jobs to the wider area.3 And there are 2.3 square metres of office space to every 1 square metre of retail space, despite (at 307,000 square metres) Leeds accounting for a quarter of all town and city centre retail space in the wider area.

Reflecting the different roles they play, the surrounding town centres have a much greater share of their space given over to retail – they are places of local consumption. This share is highest in Garforth, while Halifax has the least. There is though no clear pattern between the different groups, with Castleford and Selby having similar shares of retail to Garforth. Given the higher vacancy rates in Castleford, its higher share of space given over to retail is likely to be more precarious than in Garforth.

The use of space in Halifax and Harrogate differs from the other towns. In Halifax a much larger share of space is taken by offices (mainly Halifax bank). Meanwhile in Harrogate hotels take up a larger share of space than any other centre, while food and drink accounts for a relatively large share too, reflecting its pull for tourists.

Residential Space Composition

Getting a consistent measure of residential space in small town centres in particular is more difficult because their definitions capture to varying degrees housing on the fringe of the centre as well as within it. So what follows is based on the higher end of estimates of floorspace given over to residential.

Residential plays a large role in most town centres. In Leeds city centre it accounts for 18 per cent of all space, while on average in the towns it accounts for almost half. In Ilkley, 67 per cent of space in its town centre is residential, reflecting the high number of homes around its train station, in particular. There is no clear pattern in terms of housing across the different groups.

Other factors affecting the performance of towns

Of course, for places either to benefit from the performance of Leeds or to have strong economies in their own right depends on a number of factors, with skills one of the most significant. In Harrogate and Wetherby at least one third of residents have a degree. In Ilkley, it’s half. In Halifax, Selby and Castleford, it’s less than one in five. Without addressing the skills issues in struggling places, residents will have little chance of either accessing the prosperity in Leeds or helping to generate it where they live.

In part, the skills mix of a place is determined by how attractive it is as a place to live to higher-skilled people. Of those who commute into Leeds from outside, almost half choose to live in places with populations under 10,000 people that offer a ‘village’ lifestyle (underlining the increasing importance of Leeds to a settlement as it gets smaller). Just 16 per cent choose to live in a town sized between 10,000 and 125,000.

Where this 16 per cent of people live is revealing. Over half of them live in Harrogate, Garforth, Ilkley or Wetherby. By way of comparison, they are home to 29 per cent of all population who live in the towns used in this study. Their choices will be shaped by the ‘offer’ these places are able to make to prospective residents. This is hard to measure, but housing, crime and school performance indicators give some insight. The share of houses in higher council tax bands (used as a proxy for quality) is much higher in a place like Harrogate than Halifax. Levels of crime are lower in Garforth and Wetherby than they are in Pontefract and Castleford. And Ilkley and Harrogate have a higher share of their schools rated as ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted than Halifax, Castleford and Pontefract.

Transport also plays a role, though this is not clear cut. For example, it is quicker to drive from Pontefract to Leeds city centre than from Harrogate, while the train takes around the same amount of time (noting that the train from Harrogate is more frequent than from Pontefract). Findings from an analysis of towns around Birmingham also showed that better performing towns weren’t necessarily the ones with the fastest transport connections.4 This isn’t to suggest that better transport connects aren’t a good thing, but rather to caution against suggestions that it is the main cause of a place’s prosperity.

Conclusions

The composition and performance of any high street or town centre in a place is shaped by two things. The first, and most fundamental one, is demand, which is shaped by the amount of money that people in a place have to spend. The second one is the role that it plays in its wider area, which will determine catchment area it serves and the types of activity that can be found in it.

Looking at the area around Leeds shows this very clearly. Leeds city centre is a centre of production and consumption, and office space is the dominant use in it. Its role as a place of production is particularly important, providing prosperity for a much wider area outside of it. For places like Wetherby and Ilkley in particular, it puts money in the pockets of their residents to spend in their more retail-dominated town centres, which play the role of places of local consumption.

This makes the continued success of Leeds as a centre of the knowledge economy very important for its neighbouring towns and villages. To support this policy should encourage the further expansion of office space in its centre in particular, for which demand will likely continue to grow even in a world of more hybrid working, and make sure places around it are sufficiently connected so people can commute into it if they choose.

The success of Leeds isn’t the only factor. Harrogate shows that it is possible for a place to generate prosperity through having a strong economy in its own right. It is likely though that this is an exception rather than something every smaller place can achieve. And skills, housing and crime will all shape outcomes too. It is clear though that having a strong Leeds is a key part of improving outcomes for residents across the wider West and North Yorkshire, and for the fortunes of their local high streets.

DAC Beachcroft provides a comprehensive range of real estate services, including: development, acquisition and disposal, asset management, planning, construction and litigation. Our involvement in retail, residential, commercial, leisure and health informs our response to private and public sector clients as they seek to create vibrant and sustainable urban centres.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily the views of DAC Beachcroft. No liability is accepted to users or third parties for the use of the contents or any errors or inaccuracies therein. Professional advice should always be obtained before applying the information to particular circumstances. Click here for further details please go. Please also read our DAC Beachcroft Group privacy policy here. By reading this publication you accept that you have read, understood and agree to the terms of this disclaimer.

This work contains statistical data from ONS which is Crown Copyright. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research datasets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates.

References

*2019

1Defined as the standard occupational classifications of: 1. Managers, directors and senior officials; 2. Professional occupations; 3. Associate professional and technical occupations. This estimate is created by multiplying data from the 2019 Annual Population Survey, which is reported at the Leeds local authority level, by the share of high skilled occupations in the Leeds local authority that were in the Leeds built up area in the 2011 Census (92 per cent).

2This is done for two reasons. Conceptually, places below this size are unlikely to have much of their own economy to speak of. And methodologically it becomes more difficult to get data on high-skilled commuting for them because of the geography the data is made available at.

3Swinney P (2014): Core Strength: supporting the growth of Leeds City Centre, London: Centre for Cities

4 blog