Autonomous vehicles are being tested on public roads around the world just as the first crewless ships are being trialled in open water. Is the insurance industry ready for the potential huge shift in coverage this will entail with a switch from traditional motor accident damage and marine protection and indemnity policies to product liability and recall cover?

A world where much of our transport is fully autonomous is rapidly moving from theory to reality: driverless cars are being tested around the world, small cargo ships without crews are almost ready to be launched and planes have for many years been controlled by autopilots most of the time they are in the air. When it comes to autonomous vehicles, insurance, the laws surrounding transport and public attitudes have been racing to catch up with the almost breathless pace of development being forced by motor manufacturers.

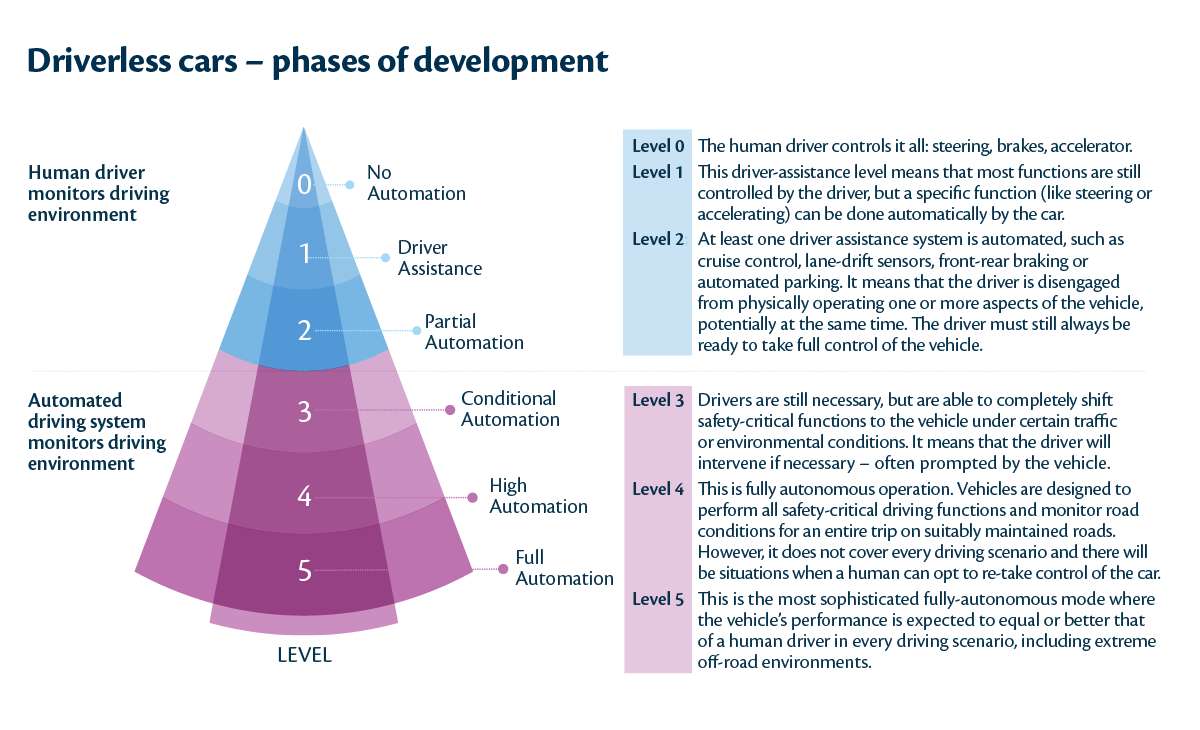

In the UK, this has brought us to the crucial level 3 stage in the development of autonomous cars where cars will be able to drive themselves, but will hand back to the driver when facing situations they can’t handle (see graphic). In Germany, the pace of change is even faster as new laws have just been passed to allow fully autonomous – level 5 – cars on public roads.

At the junction

In some ways, insurers are more comfortable with the fully autonomous vehicles than they are with the transitional phases, says Peter Allchorne, Partner at DAC Beachcroft. “Level 3 automation brings with it many risks and in many ways we would be better skipping this stage entirely. It highlights the absolute need for serious public awareness and education. When you are looking at these developmental phases that fall just short of driverless, there is a real danger that a driver could be lulled into thinking they are driverless when they should be taking control.”

This concern is shared by some major motor manufacturers. Jim McBride, autonomous vehicles expert at Ford, said recently that Ford wants to move straight to level 4, since level 3, which involves transferring control from car to human, can often pose difficulties. “We’re not going to ask the driver to instantaneously intervene. That’s not a fair proposition,” he said.

In the UK, we have to accept that many level 3 vehicles will soon be on our roads – ahead of the planned introduction of level 4 in 2021 – says David Williams, Technical Director at AXA. “I understand and share some of the concerns around level 3 operation. We would rather level 3 didn’t exist but the reality is that it does and it will soon be with us. Level 4 has similar handover concerns but the handover there is entirely at the driver’s behest.”

Williams says AXA is developing protocols and relevant safety features in the trials it is running with manufacturers in Bristol. This would lead to recommendations going to government for inclusion in legislation, including around driver training: “It should be an obligation on the manufacturers to promote training so that the driver can use the vehicle safely, especially during the handover phase”.

Allchorne agrees that driver training has to be addressed: “It is about the ‘here and now’ and that education has to happen now ahead of the advanced automation systems becoming available. It will be too late once they are on the road”.

Andrew Parker, Partner and Head of Strategic Litigation at DAC Beachcroft, says that imposing an obligation on drivers seems the obvious route to achieving this, but warns that it might meet resistance: “Developing a certificate of competence with some statutory underpinning short of an additional driving test seems the sensible course, but it wouldn’t please everyone. It could restrict the market for the products and the vehicle manufacturers would have something to say about that”.

Mapping the future

While insurers might be nervous about this transitional phase, they are much more comfortable with the way the Automated and Electric Vehicles Bill proposes dealing with the compulsory insurance obligations, says Williams: “The Bill definitely moves the conversation on in a very positive way. There will still have to be an RTA compliant policy in force and the motor insurer must handle the claims regardless of the cause and even though in some cases the driver could effectively be a passenger”.

Insurers will then have the option of pursuing recovery from a product liability or professional indemnity insurer if one of the increasingly complex parts or systems failed due to design issues or wasn’t installed properly. This won’t be automatic.

“These vehicles are going to be complex and we would still have to show that the manufacturer or installer is negligent if we are to recover from them,” continues Williams, “and they will still have the state of the art defence to rely on.”

Recovery won’t be a simple process, says Olya Melnitchouk, Senior Associate at DAC Beachcroft: “It puts the onus on the insurance company to recover from not only component manufacturers but also potentially software providers and highway authorities. There are a lot of complexities”.

Many people have assumed the main interface when it comes to recovery will be between the frontline motor insurer and the insurers of the component manufacturers, installers and repairers, but this will only be part of the story says Wendy Hopkins, Partner and Head of the Global Practice Group at DAC Beachcroft. “The interconnectivity and the ability of the vehicle to communicate effectively with the highway infrastructure is absolutely key.”

There was a recent accident involving a Tesla in autopilot mode which drove into a wall due to poorly marked lane dividers. In another trial, a driverless car stopped in the middle of the road because it came across a pothole and didn’t know what to do. “These highlight the need for a major new investment in the highway infrastructure. The authorities have a maintenance obligation now, but this is obviously a huge extension of that,” says Hopkins.

These issues will play out in a similar way in the US says Francis Manchisi, Partner and Head of Product Liability, Prevention and Government Compliance at Wilson Elser: “Apportioning liability in the US legal system will become more complicated for accidents involving autonomous vehicles – especially before the vehicles reach the level 5 stage of full automation. Did one or both of the drivers take over control of the vehicle? Should they have taken control? Did they act negligently once they did so?

“The product liability issues will not be limited to the manufacture of the autonomous vehicle. The issue of whether the software in the vehicles was defective must be examined. Did the driver/owner update the software on the vehicle to ensure that the vehicle was driven with the most recent software? What instructions/warnings were provided to the vehicle owner in this regard? The potential issues in the autonomous vehicle accident go far beyond the frequent car accident litigation cases in the US today in which a jury often determines the outcome based upon the testimony of the drivers involved.”

Data battleground

Overlaid on this increased complexity will be the additional data generated by the vehicles and the infrastructure. This is going to be a key battleground for the insurance industry, says Williams. “We want it to be shared appropriately and we think there needs to be some legal requirements put in place to ensure that happens.”

The current legislation needs to be strengthened to make sure there is clarity about how data should be shared, according to Parker: “It is going in the right direction, but it isn’t there yet. The key will be the data that will be held by the vehicle manufacturer and that will tell us whether the vehicle was operating in autonomous mode and what happened. It lies at the heart of the connected relationship and we must deal with that in a joined-up way. It certainly won’t be best to deal with it in a frictional litigation environment”.

The powerful German motor manufacturers are pressing for this exchange and sharing of data to be handled through a third-party clearing house, something that could be pushed through into European regulation. It isn’t something that would cause a problem in the UK, according to Williams as the Motor Insurers’ Bureau is already an effective central repository for a lot of third-party data.

There is a long shopping list of other issues that the industry will have to address as we move through the phases of automation, says Hopkins, with cyber liability and recall key among them. “Recall and corrective action programmes are likely to become commonplace, reflecting the increased scope for safety defects arising from a vehicle’s sensors, software and electronics.

Technological advances additionally render the vehicle vulnerable to third-party influences such as hacking, breakdown in communication networks and deficiencies in highway infrastructure. Such interdependencies beg the question ‘what is the product?’ and make it increasingly difficult for insurers to assess the underwriting risk. Global supply chains – and the analysis of where liability rests – will become ever more complex.”

It is important that people don’t get too distracted by the challenges autonomous vehicles are bringing or fall into the trap of thinking there will be a simple, single answer to all those challenges, says Williams. “Not all vehicles are going to be the same so we will need to understand the capabilities and technologies in different vehicles. But, most importantly we mustn’t lose sight of how much safer these are going to make our roads.”

Automation at seaThe marine insurance market is watching the motor market closely to see how the complex mix of liability coverage issues play out, says Toby Vallance, Senior Associate at DAC Beachcroft. “They are going to get a much longer lead time than with automated vehicles. They will also benefit from seeing how the shift to product liability will be worked out.” There are some small-scale trials of crewless ships starting, run by Rolls-Royce and by MUNIN (Maritime Unmanned Navigation through Intelligence in Networks), a European Union funded project. Rolls-Royce says it expects to launch the first remotely-operated local vessels by 2020 when it has completed the current trials in the Baltic. Following that roll-out, Rolls-Royce estimates that there will be remotely controlled coastal vessels by 2025, remotely controlled ocean-going ships by 2030 and fully autonomous, unmanned ocean-going ships by 2035.

Looking towards the horizonDespite this relatively long timeframe, governments and international maritime bodies are already turning their minds to how the laws of the sea and associated regulations will need to evolve. Vallance says many of the legal and regulatory issues are being worked on in the UK in the Maritime Autonomous Systems Regulatory Working Group which is due to report shortly to the Maritime and Coastguard Agency. From there, the discussion will go global at the International Maritime Organisation. Recognising the growing demand for regulatory support for unmanned vessels, the international classification society Lloyd’s Register announced on 13 June 2017 that it has launched the LR Unmanned Marine Systems Code, which it says provides a goal-based code that takes a structured approach to the assessment of unmanned marine systems against a set of safety and operational performance requirements. Currently crew safety is a big driver behind maritime regulation. Consequently, the advent of crewless vessels will lead to a significant shift in regulation. Vallance says the priority will move from crew safety to vessel security, particularly in the context of cyber risk. Concerns around the risk of cyber attack will lead to stringent cyber security requirements if fully or even semi-autonomous vessels will be allowed to operate in the open seas. He says he has been disappointed by the relative lack of engagement: “I’m not sure the shipping industry has come to terms with the concept of not having humans on board.” This means some tricky issues, such as mechanical failure, are not high enough up the agenda. “The issue that hasn’t been dealt with, is what happens if something goes wrong mechanically. Ships at the moment have engineers on board who can make running repairs but what happens when a crewless ship breaks down in bad weather, potentially drifting for 24 hours?” |